Introduction

I began my professional career in the IT industry when the DevOps culture was already well-established. It had been nine years since Patrick Debois published the video dev meets ops, ops meet dev on YouTube.

I’ve always envied those who were fortunate enough to enter this field in the early 2000s when we weren’t bombarded with tools like we are now. Back then, you had a Linux Kernel, a few bash scripts, and manuals. What I envy the most, perhaps, are those manuals. If you wanted to learn something, you bought a manual and studied it. I believe this is one of the reasons why those who started in those years have such solid foundations.

The RTFM generation.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not that you can’t do it now. I’m not blaming my numerous gaps in knowledge on the limited information available today. The problem today, I believe, is that there’s too much information. Too much noise.

I’m also responsible for this by writing in this blog. I’m just a nobody consuming your bandwidth and server computing power to write something that probably won’t enrich you.

True, there was less information floating around back then. But damn, it would have been fun.

I’ve been in this industry for years, and I’ve noticed that with all these tools, we often lose our way and bounce aimlessly from one tool to another.

But the DevOps philosophy isn’t about tools, it’s about processes.

And, to be honest, we can’t even say that Debois “invented” it. Debois coined the term.

But system administrators and developers trying to automate as many processes as possible were already DevOps before 2009, they just didn’t know it. (Poor them, if they had known, they could have commanded annual salaries of > $100k.)

So, what does the DevOps philosophy have to do with this? The primary aim of DevOps, according to the DevOps library history, is to maximize the efficiency, predictability, maintainability, and security of operational processes. DevOps was primarily introduced to fix the inefficiencies of the Waterfall method such as:

- A lower failure rate of newly released software.

- A faster mean time for recovery if a new release crashes or gets disabled in the current system.

- A shorter lead time between fixes.

- Increased frequency of deployment.

This has nothing to do with tools, tools are merely the means to achieve this goal

And looking around now, I find myself inundated with tools.

Those entering the job market now may start using tools like Docker, Kubernetes, and managed cloud services right away.

But all these are nothing but layers of abstraction. Abstraction upon abstraction upon abstraction.

Think about it.

Containers, one of the biggest software development revolutions of the last 10 years, are just cgroups and namespaces! Kubernetes? Just containers and a lot of networking. Cloud instances? Just a Linux kernel running somewhere!

I could give you dozens of examples like these.

The goal

However, this time, I don’t want to stop at merely envying the old guard of information technology. I want to put myself in their shoes twenty years ago and try to do something I do every day using only the tools they had.

I want to retrace the various phases experienced by those who deployed something in the last twenty years.

I could do this by sampling once every five years, thus performing the same deployment as if it were 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. And what could I deploy? How about something that has already been put into production? What do you think about my website?

Some time ago, I wrote this article How to deploy your own website on AWS with Terraform and GitHub Actions! and included a lot of fancy stuff: Infrastructure as Code with Terraform, site distribution through a CDN, and an S3 bucket on AWS for hosting static content, a pipeline with GitHub Actions for automatic builds and deployment upon push to a Git repository.

Would I have achieved the same result if I had hosted my website on a Raspberry Pi? Sure! Of course, I wouldn’t have been able to maintain the SLA that an Amazon S3 bucket provides without cross-region replicas (99.99%). Think about it, these are crazy numbers for a long-haired guy self-hosting his website. We’re talking about a maximum downtime of 52m 9.8s per year!

In the next episode, we’ll try to put ourselves in the shoes of a “DevOps,” one of those who didn’t know they were in the early 2000s. And we’ll try to deploy our website as if it were those years, without all the tools we have now!

If you have any ideas for the title, let me know! For now, I thought of “How to deploy your site, but it’s the early 2000s.”

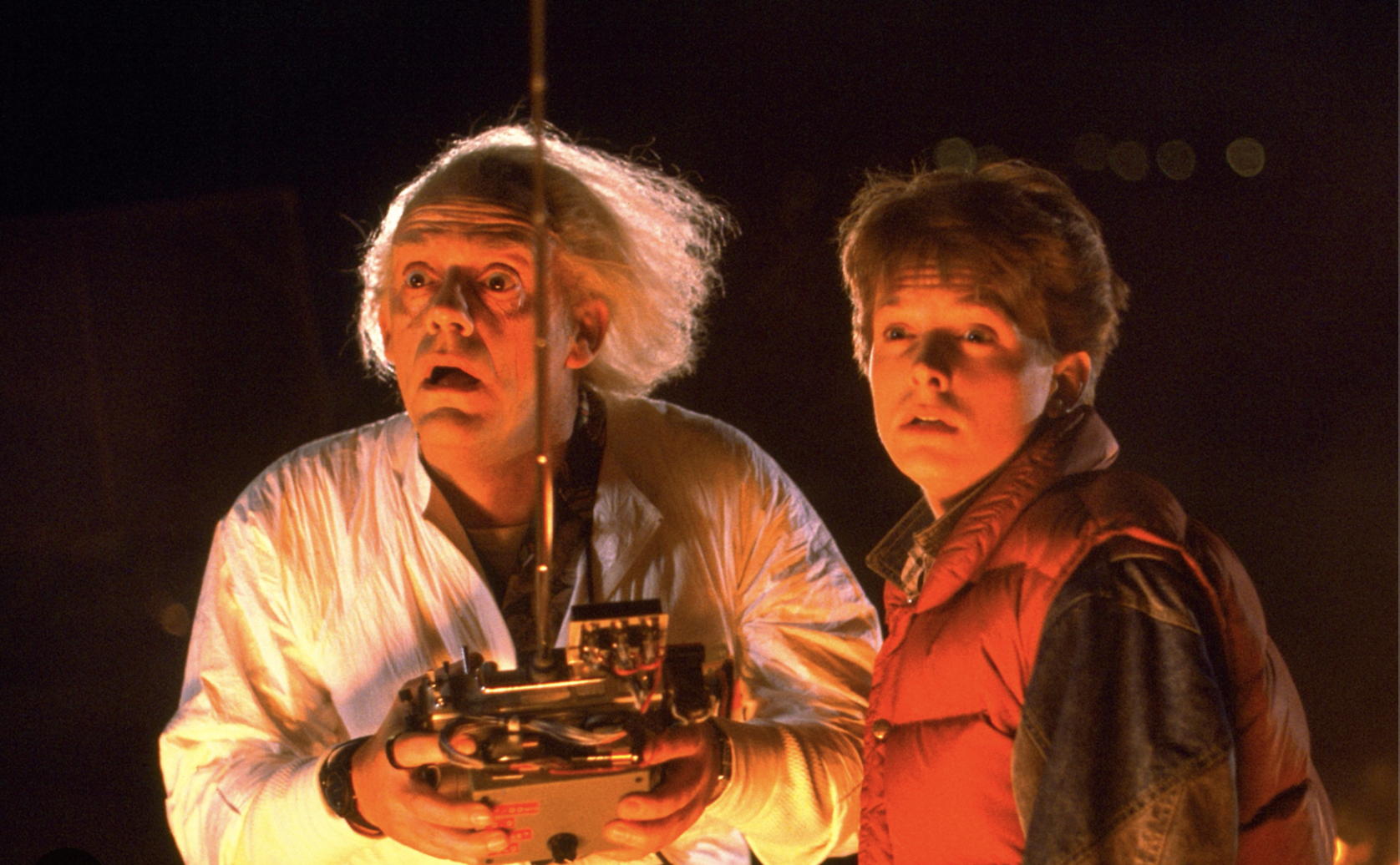

Do you need a ride? 😉